I don’t like recommending things.

Not movies. Not restaurants. Not even a decent bottle of red. Why? Because what if you don’t like it? What if you watch it, eat it, drink it and go, “Aye… that was rubbish, actually.” Then I’m the clown who mugged you off. And I’ll carry that shame for years. My social anxiety simply won’t allow it.

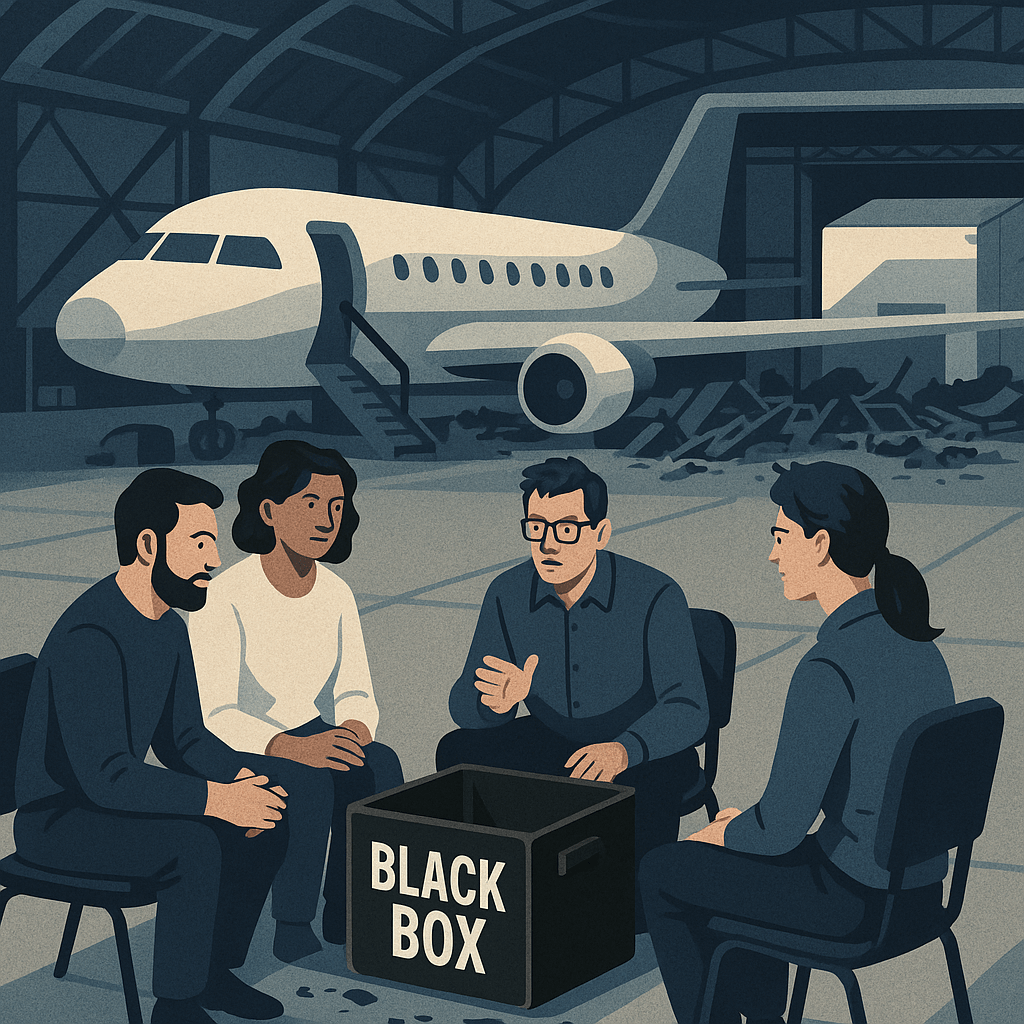

But this book Black Box Thinking by Matthew Syed is different.

It’s the only book on failure that didn’t make me feel like a failure for reading it. It changed the way I think about mistakes, especially in teams and tech. If you work in software, and especially if you run retrospectives, you need this mindset. Honestly. It’s that good. It’s not like the first time I heard The Beatles but its still a good book.

So yes, I’m recommending it, you’ve probably read it, its like famous but I still want to talk about it. If you hate it… please don’t tell me.

What’s Black Box Thinking?

Matthew Syed starts with aviation. When planes crash, investigators don’t waste time blaming the pilot and moving on. They study the black box, the flight data recorder for the uninitiated, to understand exactly what happened. Then they feed that learning back into the system. Over time, this has made flying one of the safest ways to travel.

Now compare that to healthcare, business, or tech, where failure is often buried, explained away, or quietly ignored so no one looks bad. Should a culprit be discovered or a goat scaped they feel the full brunt of corporate life (a letter or something)

The core message of the book is simple but powerful: Failure isn’t something to avoid. It’s information. It’s feedback. It’s progress in disguise.

Meanwhile, in Retro Land…

Now let’s talk about retrospectives. You know the drill:

- Sprint ends.

- We get everyone in a room – cause its 2019 – probs a Zoom.

- We ask what went well, what didn’t, and what we’ll try next time.

- Someone mentions Jira tickets.

- Someone else mentions “communication”.

- Product blames engineering

- Engineering blames product

- We nod. We smile. We move on.

But do we actually learn anything? Do we do anything differently?

Or are we just politely crashing the same plane over and over again? (#metaphor)

Why Most Retros Don’t Work

Here’s where Black Box Thinking hit me like a tonne of Agile bricks.

Retros fail when they become a performance instead of a process. When we:

- Sugar-coat mistakes to protect egos or reputations.

- Focus on who should’ve done what, instead of what the system allowed.

- Collect action items like Pokémon, but never evolve them.

- Forget that trust is oxygen for truth. Without it, no one will speak up.

And the worst part? When we don’t learn from failure, we waste it.

Retros as Flight Data Recorders

So what would it look like to bring Black Box Thinking into our retrospectives?

1. Ditch the Blame, Fix the Process

Don’t ask “Who broke it?“Ask “What made it breakable?”

Get curious about the system. Make it clear that we’re not here to point fingers, we’re here to find levers.

2. Make Failure Visible

Celebrate near-misses. Document outages. Share the bug that got all the way to production.

Not to shame anyone but to build muscle memory around learning.

3. Close the Loop

Stop letting action items fade into the sprint backlog abyss.

Follow up. Did that thing we said we’d do actually help? Are we repeating old mistakes or building new resilience?

4. Write It Down (and Look Back!)

Treat retro notes like flight data. Store them somewhere visible. Review them occasionally. Spot patterns.

(And no, “Confluence” doesn’t count unless someone actually reads it. Does a digital all points board exist?)

5. Facilitate Like an Investigator

When you’re running a retro, channel your inner crash investigator:

- Stay neutral.

- Ask open-ended questions.

- Dig deeper than the first answer.

- Look for systemic issues, not personal ones.

You’re not Judge Judy. You’re here to learn.

What We’re Really Trying to Do

The point of retros isn’t to pat ourselves on the back or assign homework.It’s to build a culture where mistakes become momentum.

We want teams that feel safe enough to be honest.Processes that are robust enough to change.And systems that get better over time, not just faster at hiding problems.

Final Approach: Try It at Your Next Retro

So, if you’re running a retro this week, bring one Black Box principle into it. Maybe you:

- Reframe how you talk about failure.

- Track whether last retro’s actions actually moved the needle.

- Just ask, “What did we learn that we didn’t know before?”

Small changes, big lift.

Your team doesn’t need a hero. It needs a culture that learns.

P.S. Have you ever wondered why on every plane, regardless of the carrier, they always say “cabin crew – arm doors and crosscheck”, that is cool and probably came out of an investigation with a black box.